100: Interest Rates & Bank Balance Sheets

Thinking through the fair value of loans and the equity value of banks.

You’re reading the weekly free version of Watchlist Investing on Substack. If you’re not already subscribed, click here to join 2,500 others.

Want more in-depth and focused analysis on good businesses? Check out some sample issues of Watchlist Investing Deep Dives, a separate paid service.

For $20.75 per month, you can join corporate executives, professional money managers, and students of value investing receiving 10-12 issues per year. In addition, you’ll gain access to the archives, now 24 issues and growing!

A *Fair*ly large hole in the balance sheet

The ongoing stress in the banking system is largely a result of the question of how changes in the value of assets impact the safety of depositors and shareholder value.

Banks are highly levered institutions by their very nature. Even an unusually conservative bank with a capital ratio of 20% is leveraged 5x.

Look at what happens when the value of assets declines: A 10% decline in the value of assets (liabilities are always rock-solid) leads to a jump from 5x to 9x leverage. A decline of 20% wipes out equity entirely.

There are many ways in which bank assets can decline in value. One is through credit losses where banks lend too much and can’t recover their capital from a borrower or the underlying collateral. Think 2008/09 and the GFC.

Another is if interest rates rise. As the famously-annoying tagline goes: bond yields move inversely with prices. Silicon Valley Bank held assets with very little credit risk. But they had a ton of interest rate risk because they bought long-term securities whose value is highly sensitive to changes in interest rates.

Investors realized that the fair value of SVB’s assets declined to such a degree that a forced sale would wipe out equity capital. It was the scenario on the right from the example above. Depositors, many of whom had uninsured deposits, fled the bank. This caused (or would necessitate) a forced sale of assets to meet redemptions, which depositors rightly realized SVB could not meet if its assets were insufficient. The result: FDIC receivership and a total wipeout of shareholders’ equity.

Accounting is important!!!

Enter the jargon AFS (available for sale) and HTM (held to maturity). AFS assets are marked to market. If interest rates change the value of these assets is adjusted accordingly. HTM assets remain on the books at amortized cost or carrying value. Silicon Valley Bank reported $16 billion of equity capital at the end of 2022, but the adjustment for the difference between the fair value of its HTM portfolio and its carrying value wiped out the equity account.

What about loans?

Loans are bank assets with economically equivalent characteristics to securities. Most banks aren’t in the business of selling loans so they hold them at carrying value - in other words, they expect to hold them to maturity.

So many questions…

How should bank investors think about loans?

Should changes in their fair values be ignored? If so, when?

How should one assess the risk of deposit flight?

Should adjustments be made to the income account or balance sheet to reflect changes in their values?

If no change in equity capital occurs is the bank’s intermediate or long-term earning power affected?

Thinking it through with numbers

Imagine a super simple bank as follows: It has one asset (a loan) with a fixed rate of interest. It funds that loan through equity capital and noninterest-bearing deposits. What is the value of the bank?

Let’s use the bank from above. Let’s say it has a $1mm loan at 3.5% amortized over 25 years with a maturity or rate reset after five years. This might be your typical low LTV loan originated to a strong sponsor a few years ago.

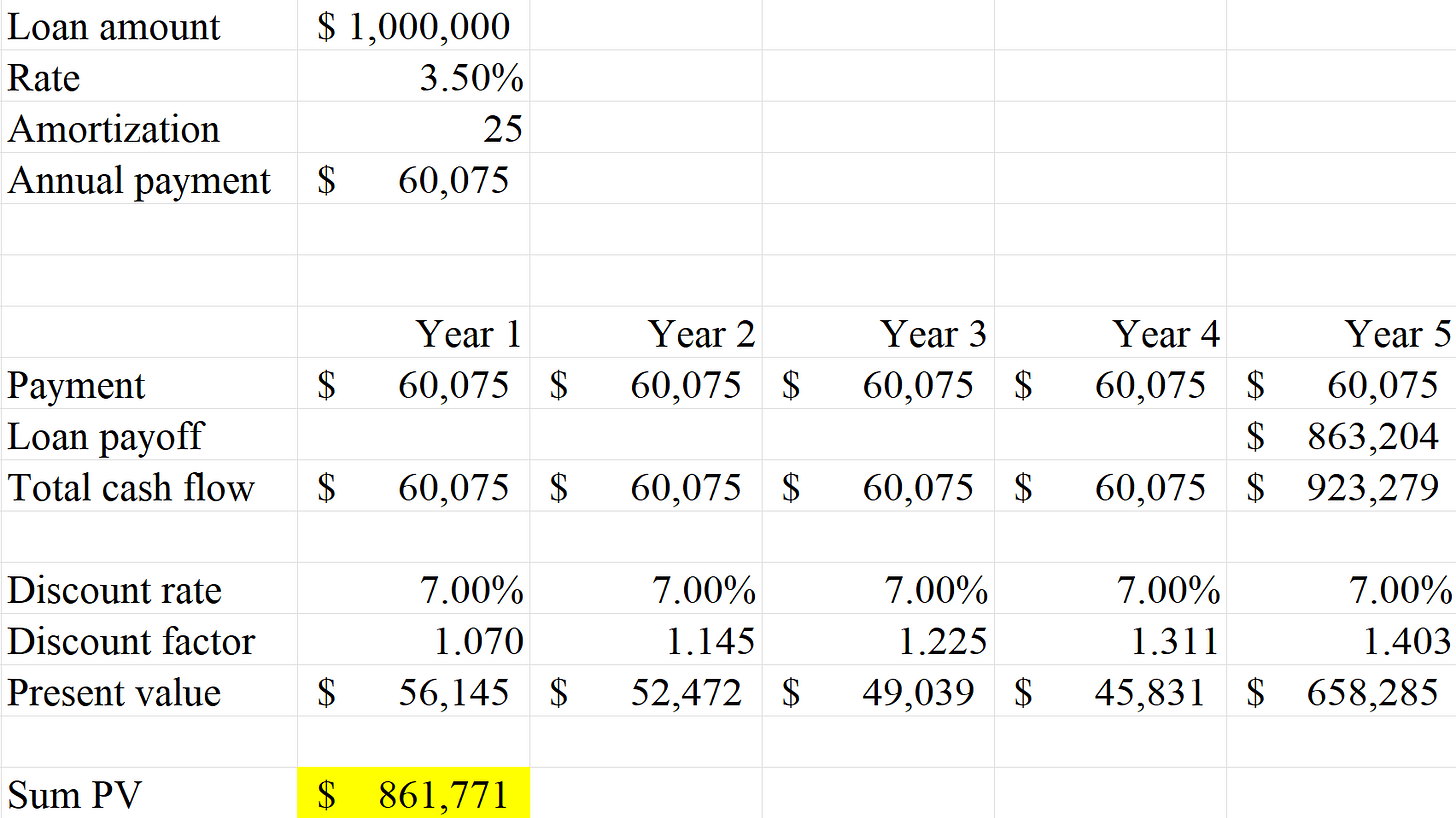

Here’s what the cash flows would look like. My Excel math is off slightly in that the present value of the loan discounted at the rate of the loan should result in par. It’s close enough.

Now let’s take those same payments but discount them at a 7.00% interest rate. We’re assuming market rates have gone up and therefore the value of the payments must go down.

That’s a 14% decline in the value of the loan. Here’s what it would have done to the balance sheet if we were marking it to market:

Does vantage point matter?

Has the value of the bank changed to the shareholder? Let’s assume I use a 10% discount rate to look at equity investments. The cash flows from the loan have not changed at all. Let’s make it even simpler and assume it was an interest-only loan at 3.5%. The bank is still earning ~$35k per year in interest income.

If interest rates go up and I still use that same 10% discount rate to value the cash flows then the value of the bank has not changed at all. This holds true even if the market value of the asset fluctuates widely.

It’s only if I change the rate I demand as an equity investor that the value of the bank changes. Now, in reality, banks have funding costs that change with the general rate of interest. The $35k interest income above might have cost me 0.50% when originated, meaning I had a 3% net interest margin. If rates go up to 3.5% then my interest costs will eat up my interest income.

Return of capital - a critical component

We go even deeper. The original loan scenario laid out above was an amortizing loan. Interest is paid in addition to the principal. This return of capital is very important. If you face very low credit risk then you can count on getting some of your original investment back each month or year as the loan pays down. You’ll also collect the full amount due at loan maturity. Or, as is typical, the loan will reset at the five or seven-year mark. This is economically equivalent to making a brand new loan at market rates, so it’s okay (I think) to model a full payoff at the reset date.

So you have a return of capital component that offsets some of the risks of rising rates. (You can re-lend that money at current market rates.)

What about depositors?

How do depositors behave and how should equity investors think about depositors? Crucially, the scenario above assumes the bank can hold the loan to maturity. Whether the loan is on the balance sheet at amortized cost or market value the cash flows remain the same. But a depositor has to worry about getting their money back.

If I’m a big depositor of that $800k in liabilities I’d want to know what my risks are. If I think others might withdraw their money from the bank I’d want to know that the institution can pay them AND pay me. A sudden rush for the exits that necessitates the sale of assets at a lower market price or even distressed prices could mean there isn’t enough leftover to pay depositors in full.

The paradox

We have a sort of paradox then. A decline in the value of a bank asset is not in itself enough to cause trouble.

A problem only arises if the bank cannot sell or must sell at a steep discount an asset to fund redemptions, or if contractual cash flows do not materialize.

If depositors in the bank above had 100% assurances that their money would be paid then the bank could hold the asset as long as it wished. Provided, however, that interest and noninterest expenses didn’t consume all interest income and the bank was sufficiently capitalized to weather the storm.

Putting it all together - my current thinking

I think it is important to view the issue of fluctuating bank asset values through two lenses. One is through the eyes of the depositor. It is critically important to a depositor that they get their money back. If a bank’s assets decline in value such that it impairs a creditor’s ability to get their money back, a crisis of confidence might occur and a run on the bank could be the result. Therefore, adjusting all bank assets to market value is an important exercise. If the bank remains adequately capitalized then depositors shouldn’t worry and equity holders can avoid seeing their investment turn to ashes.

So long as the depositor is satisfied - or should have reason to be satisfied - that the bank is sound, the value of the bank to the equity holder depends on what happens with cash flows and net interest income. How long the scenario persists and the magnitude of the changes are variables the investor must estimate to determine the value of the bank.

And assuming that the loans are paid as agreed, the original book value of bank equity capital will remain intact and allow future lending at similar leverage ratios. In other words, one can adjust equity capital to market, but that doesn’t mean the bank has suffered a permanent decline in its equity account - and consequently, its ability to hold a similar level of assets in the future. (In the example above, the bank wouldn’t be restricted to levering $62k equity capital, it would still have $200k.)

A call for good thinkers

If you’re a bank investor I’d love to hear from you. How is my thinking? What did I get wrong? What banks and/or time periods should I look at to see how these scenarios might play out in real-time?

Thanks, and as always…

Stay rational! —Adam

P.S. Photo by Ferran Fusalba Roselló on Unsplash

Agree. In light of all this, I think HIFS could be a very attractive investment at these prices. I'm averaging down at the moment. Any thoughts about it?

P.S. The 'Theory 1 and 2' of banking framework from Matt Levine is useful for thinking about this too.

You're welcome!