32: Does Warren Buffett Think In Yields?; Inside of a Maple Tree; The Double-Deluded Analyst; Hungarian Nanocap Liquor Company

I found a gem inside the 1997 BRK annual meeting.

You’re reading the weekly free version of Watchlist Investing. If you’re not already subscribed, click here to join 850 others.

Want more in-depth and focused analysis on good businesses? Check out some sample issues of Watchlist Investing Deep Dives.

For less than $17/month, you can join corporate executives, professional money managers, and students of value investing receiving 10-12 issues per year. In addition, you’ll gain access to the growing archives.

The Double-Deluded Analyst

I came across a post on a fairly well-respected investing site that made me shake my head. The site and the company aren’t important. It was the way in which the writer phrased the value proposition that made me cringe. Here’s the gist of it:

“ … we can purchase shares at 2.8x 2026 base case EBITDA … ”

I’m sorry, what? First of all, I hate EBITDA. Depreciation is a real expense. Enough said.

Second, and my main gripe, this post was written in 2021. Buying something based on next year’s cash flow is a sound way of looking at things and underlies DCF models. Outlay cash today at Period 0, get some cash at Period 1 for some return. But five years out? No one talks like that (at least that I’m aware of). What about the time value of money?

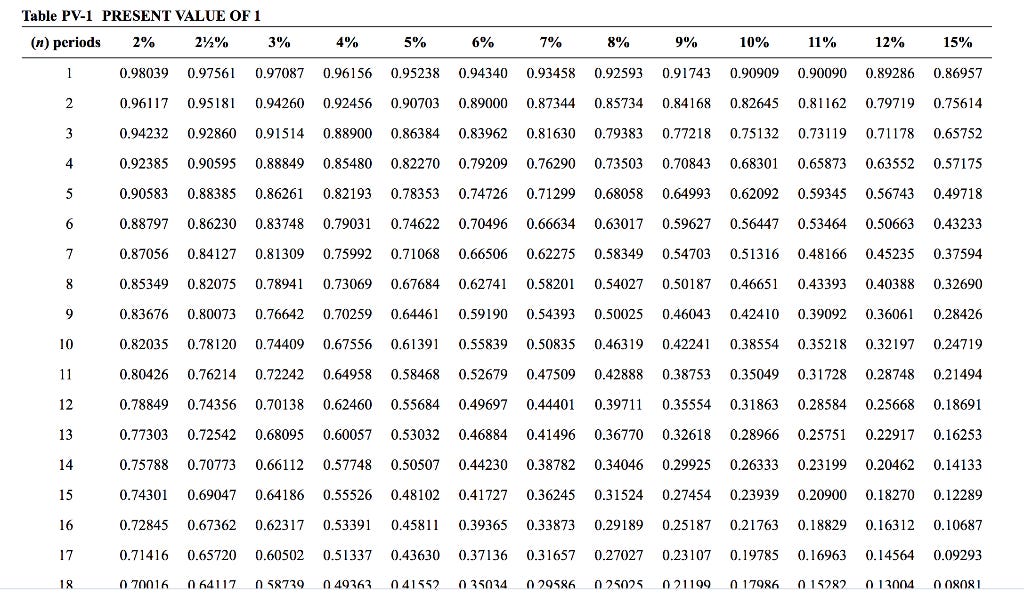

Let’s bring in a handy present value table. I’ll be generous and only assume a 7% expected return. That 2.8x five years out means you’re paying 2.8x / 0.71 = 3.9x in today’s terms. Want 10%, that’s 4.5x. The numbers didn’t move a ton but the basic point is the analysis was, in my view, off base.

The writer deluded themselves twice: once by using EBITDA in the calculation and again by distorting the time element.

Does Warren Buffett Think In Yields?

Speaking of returns …

In working my way through the 1997 Berkshire Hathaway annual meeting I came across this subtle comment by Buffett (bolded for emphasis):

“And, obviously, we can always buy the government bonds. So that becomes the yardstick rate. It doesn’t mean we want to buy government bonds. It doesn’t mean we want to buy government bonds if the best thing we can find is only — has a present value that works out at a half percent a year better than the government bond. But it’s the appropriate yardstick, in our view, to simply use to compare across all kinds of investment opportunities, oil wells, farms, whatever it may be. Now, it gets into degree of certainty, too. But it’s the yardstick rate. It’s not because we want to buy government bonds. But it does serve to make that a constant throughout the valuation process.”

What is Buffett saying here? He’s saying you have to think in terms of annual returns and compare those returns to the government rate. It’s not enough to say ‘I can buy this company at X-Price and it’s worth Y-Value’. It’s not the absolute difference that matters because, as noted earlier, time matters. What really counts is the annualized return.

When valuing a business Buffett probably thinks in terms of both absolute dollars and yield. Meaning, if he’s looking for a 10% return he’ll say ‘I can pay this much for this business’. But he probably also looks at it and says, ‘At such and such a price I can expect this yield. Government bonds are here and I want a margin of safety of a few percentage points a year. Knowing these pieces of information I can compare alternative investments and decide on a course of action’.

Now, I’ve had no direct access to Buffett to confirm this. It’s just a hypothesis based on what I’ve heard him say over the years.

What do you think? Can value investors think almost entirely in yield? Or do we need to come to a dollar amount (or range) for an investment’s worth?

Inside of a Maple Tree

During high school, I cut, split, and sold firewood. It’s tough work. The experience taught me a lot about business, but that’s a story for another day.

We have an acre lot in New Hampshire that provides a decent amount of firewood for the occasional fire in our fireplace. I enjoy the work because it’s not “work” anymore.

This weekend I was splitting an old maple that I took down last year when out popped this gem (photo below). We all know trees grow in stages and can count the rings and compute how old it is. This maple split in such a way that you could see the younger version of it poking out. You can see the maybe ten-year-old maple alongside its older self like one of those photos-in-a-photo where a person holds a picture of themselves from years ago.

It also got me thinking philosophically for a minute about how our younger selves reside inside the grown-up, etc. You can go down that road too or just enjoy a cool firewood pic!

Hungary For Some Liquor?

I came across a small Hungarian spirits company called Zwack Unicum Plc. The company’s namesake liquor is Unicum, which apparently is the national drink of Hungary.

The company’s financials are presented in Forints, Hungary’s currency. As of FYE 3/31/21 the company had total assets of 13bn Forints or about USD $40m. It earned 1.7bn Forints or $5m. Zwack is 26% owned by Diageo, the beer and spirits giant.

Stay rational! —Adam

Inside of a Maple Tree- Great Picture! Amazing!

Re: thinking in yields:

Firstly, I think calculating the (annual) yields of (potential) investments make them comparable (obviously; I mean you can translate every P/E ratio into a yield by just switiching the numerator and the denominator). And comparability (of yields) potentially plays a huge role in the capital allocation decision.

Secondly, as you mentioned, and that ties into the deluded analyst "fallacy", especially time but also the gravity of finance (aka interest rates) are the key factors for any investment decision. Buffett elaborates this in the 2000 GAM: a bird in the hand vs two in the bush (Link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vo_TWaV6Xy8). It all comes back to the expected rate of return (aka yield) for the investment (and this includes an assumption on how long it will take – which can be difficult to determine - to realise the absolute return). And there you have it: you would need to have a valuation range and also make an assumption (or having some degree of conviction) about the investment's time horizon so you can calculate the yield. Only then you can compare different investments to each other (see opportunity cost). I think, the time horizon is very much linked to the investor’s assumptions about the durability of the moat as well. Because the moat protects (and ideally grows) the intrinsic value of a company, an investor might be willing to pay more now for future cash flows, clearly anticipating that he/she must hold the investment for a longer period of time to generate the same yield as a more short-term situation (e.g. workout, liquidation, etc.) would.

Again, since time is already incorporated in yields, it makes investements truly comparable.