34: The Bruce Greenwald Methodology For Valuing Growth Companies

Applying the method to Fastenal (FAST)

You’re reading the weekly free version of Watchlist Investing. If you’re not already subscribed, click here to join 850 others.

Want more in-depth and focused analysis on good businesses? Check out some sample issues of Watchlist Investing Deep Dives.

For less than $17/month, you can join corporate executives, professional money managers, and students of value investing receiving 10-12 issues per year. In addition, you’ll gain access to the growing archives.

Bruce Greenwald Valuation Method

I’ve received a few comments on the valuation methodology used beginning in the September issue to value SAM (September), ODFL (October), and FAST (November). I chose it because I needed a framework to look at faster-growing companies but dislike using DCF models (insert Charlie Munger’s raisins comment here …). The methodology comes from Bruce Greenwald’s Value Investing: From Graham to Buffett and Beyond, 2nd ed.

Bruce Greenwald is one of my favorite value investors. Greenwald long taught the course at Columbia Business School that Benjamin Graham taught (and which Buffett took during his time there). Greenwald’s former students include Todd Combs and LiLu, among other respected value investors. He’s also a practitioner. He’s an advisor to First Eagle Investment Management.

Greenwald’s approach to valuing growth stocks is to break the valuation into component parts:

Cash return on current earnings power

Organic growth

Active investment growth

The exercise doesn’t come up with a precise figure for value. Rather it provides a return that can be compared to other investment opportunities.

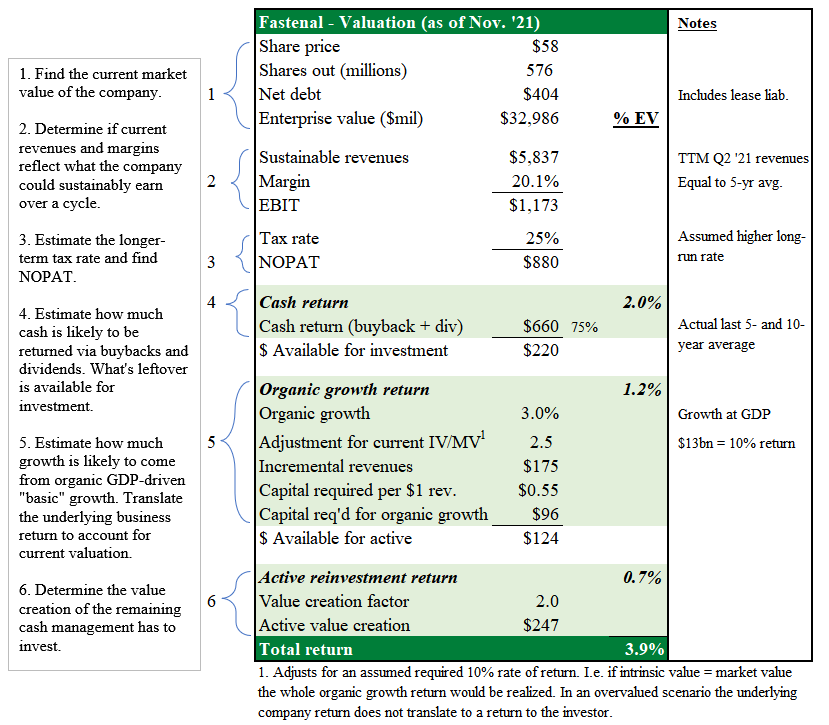

I’ll walk through how I approached FAST using the annotated table below:

Enterprise value: This is the starting point from which the returns are calculated. Share price times shares out plus/minus net debt gives you enterprise value, or what you’d have to pay to buy the company in its totality, debt and equity included. FAST has very little debt but I did make the decision to include lease liabilities. Purchasing FAST lock, stock, and barrel would cost us about $33bn at present prices.

Sustainable revenues and margin: This step requires some subjectivity but isn’t too complicated. Unless revenues are very cyclical or currently depressed, current revenues can generally suffice for sustainable revenues. Margins are generally the place to adjust for cyclicality, if any, and can incorporate any recent trends or outlook for probable future margins. Note that growth isn’t of concern here because we’re chiefly concerned about today. We’re asking, ‘what could this company earn now?’

For FAST I simply used trailing twelve-month revenues as a sustainable basis for revenues. The company’s pre-tax margins have been extremely consistent, so I felt its five-year average of 20.1% was reasonable. Multiplying the two numbers gives us $1.173bn of EBIT.

Tax rate / NOPAT: Again, some subjectivity but nothing you’re likely to be too wrong on. I chose to use 25% because I expect slightly higher effective tax rates in the future. That gives us $880m of NOPAT for FAST.

Cash return: As a quick gut-check I like to take NOPAT and divide it into the enterprise value. This tells us what we’d earn if the company distributed all its earnings to owners. With FAST this comes out to less than 2.7%, which is a paltry return. That means the company must grow significantly to justify its current valuation, a feat made that much harder considering its payout ratio.

FAST has historically distributed about 75% of earnings in the form of dividends and buybacks. It seemed reasonable to assume that would continue in the future. The $660m figure listed in the table is simply the $880m NOPAT times 75%.

Organic growth return: There are certain nuances that can be applied here, but generally organic growth will approximate GDP growth in the long run. This is growth a company would reasonably be expected to capture as the rising tide of GDP lifts all industry participants.

An important point here is that all growth, even this organic growth, requires capital investment. For FAST to grow 3% its revenues would have to increase $175m. I determined via my analysis of its financial statements that each $1 of revenue growth required $0.55 of capital investment to support it. Multiplying $175m by 0.55 tells us FAST will need to invest $96m to support that 3% growth.

Growth of the underlying business only translates into investor returns if the stock is purchased at intrinsic value. And yet a paradox exists here because we’re trying to estimate IV and yet need the figure to make an adjustment. The way I’ve tackled this is to fiddle with the enterprise value figure until it gives me a 10% return. With FAST that came out to about $13bn. That means the $33bn current enterprise value is about 2.5 times too high. As a result, the 3% underlying business growth will only translate into 3% / 2.5 = 1.2% return if purchased at the $33bn enterprise price.

Active reinvestment return: What’s left over is available to management for active investment, in this case, $124m. Here’s where the company’s history, culture, and management commentary really come into play. The ‘what will they do with the money’ question is important. It’s not as critical with FAST because it pays out such a large proportion of its earnings, but it can be a large driver of returns in other instances.

Active reinvestment returns only add value to companies with a sustainable competitive advantage (i.e. moat). At worst they can destroy value.

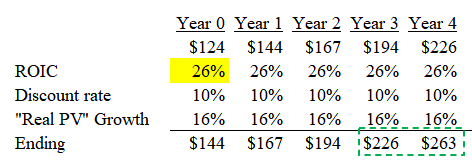

It’s here we arrive at the necessity of introducing what looks suspiciously like a DCF model, which I said I don’t like. What it really represents is a compounding of present value of just the reinvested portion of the current year’s earnings. In FAST’s case, its ROIC of 26% (conservative) edges ahead of a 10% discount rate by 16% annually. It takes less than four years to double, hence the value creation factor of 2.

The question I asked myself was, can FAST reinvest $124m of today’s cash and grow it on a present value basis by 16% per year? That doesn’t seem unreasonable given the company’s history of good returns and the prospects of investment in new technologies I identified in my analysis of the company.

One can also see the sensitivity of this active reinvestment explicitly. If I change the factor to 1.0, it only cuts the current return by 35 basis points. I can conclude that this isn’t a big driver of returns.

Summing up: Combining the cash return, organic growth return, and active reinvestment return I got 3.9%. That’s hardly anything to get excited about. Especially considering other factors which I didn’t go into here, such as what Greenwald calls franchise fade, or the tendency of moats to succumb to competitive pressures over time.

Buying FAST at $33bn assumes a lot of things need to go right.

Stay rational! —Adam

Your write: "And yet a paradox exists here because we’re trying to estimate IV and yet need the figure to make an adjustment. The way I’ve tackled this is to fiddle with the enterprise value figure until it gives me a 10% return. With FAST that came out to about $13bn. That means the $33bn current enterprise value is about 2.5 times too high. "

Tackling a circular argument by making an absurd assumption does not solve anything. If you need IV to solve for IV then you are doing something wrongly. Rather than compound the error by adding an assumption, you should stop and examine your process.

The end result is you have the market paying 2.5x too much. This sort of "I can be correct in calculating IV and completely ignore the market's valuation" because I think I am rational and the market is irrational is precisely what gets people into trouble. The assumption and the conclusion are both silly. Why would you need a 10% earnings yield to own a company with a 30% return on equity, with little debt compounding at 8% per annum? I agree you might like it - but would you demand it?

How about this instead: if Fastenal can compound sales at 8% per annum, maintaining a 20% EBIT margin, paying a 25% tax rate and re-investing about 25% of profits then it should earn about USD 1.5 billion profits in 5 years time. That's about a 5% yield on today's EV. Throw in dividends of 2.5% per annum. Instead of asking if this is right, ask if it seems very wrong. Does it? Not to me.

Hi, regarding the organic growth, I wonder whether to use the nominal GDP growth or the real one (nominal - inflation)? which one (nominal or real one) should i use to calculate organic growth return?

I have one more question. If I wanted to estimate future organic growth based on data from previous years. Let's say the average revenue growth rate of the company is 12% over the last five years. Average net income growth is 13% over the last 5 yeras. Should I subtract the average inflation over the last five years from these numbers and then and then add it to the Greenwald's formula?

If I don't subtract inflation from GDP or historical data (revenue, net income), it seems to me that the returns from organic growth are too high.