You’re reading the weekly free version of Watchlist Investing. If you’re not already subscribed, click here to join 1,200 others.

Want more in-depth and focused analysis on good businesses? Check out some sample issues of Watchlist Investing Deep Dives.

For less than $17/month, you can join corporate executives, professional money managers, and students of value investing receiving 10-12 issues per year. In addition, you’ll gain access to the growing archives.

I’m currently drafting the April issue of Watchlist Investing Deep Dives, the subject of which is Berkshire Hathaway. I came across some material on the early conglomerates that never made it into my book.

Please consider sharing this post on social media. Thank you and enjoy!

The Pre-Conglomerate Era

Prior to the age of conglomerates, business was conducted in a narrow and specialized way. As Robert Sobel wrote in The Rise and Fall of the Conglomerate Kings, “The name of the corporation told you its business: United States Steel, General Motors, Dow Chemical, General Foods, American Tobacco, American Sugar Refining, and so on.”

Even going back hundreds or thousands of years to the merchants of colonial or ancient times we find businesses engaged in basically one activity. Cloth traders, wine traders, tea traders, and so on, conducted business in one field. Those enterprises might have been funded by wealthy merchants or individuals with diverse interests of their own. But the activities of each business rarely mingled. Surely the financier of two distinct businesses would find ways for each to benefit from the other, but there was no uniting force other than the backers.

We see this separation in the legal structures of early businesses. The more modern corporation, with its stock form, has its roots in shipping ventures. Individuals would pool their capital for one specific purpose, such as a voyage to trade tea, and the enterprise would disband upon return. The ventures would have to be chartered by the government or monarch. Even today, businesses must be chartered by a government of some kind to be afforded certain legal protections. We see evidence of the early days of business in the capital businesses were authorized to hold. Retaining earnings meant seeking approval from a government to increase their authorized capital.

Businesses in the 1800s and early 1900s could grow quite large. The giants of industry such as Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, Sr., and Cornelius Vanderbilt, among others, created huge businesses to be sure. Their success was contained within a particular industry as they grew to the point of requiring anti-trust laws. Those businesses were the result of expansion into directly-related areas of operation, such as acquiring a supplier or distributor (vertical expansion). Or, they acquired competitors in the same industry (horizontal expansion). Once more we see the financial backers such as John Pierpont Morgan, Sr. that connected industries through their capital. But no attempt was made to combine diverse businesses under one roof to gain something more than the sum of their parts. That story begins in the early 1900s.

The Conglomerate Emerges

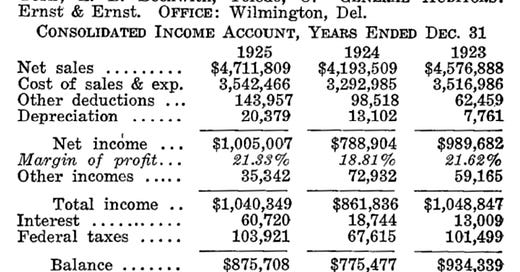

The first true conglomerate I’ve been able to find is American Home Products. The company was formed in 1926 and grew by acquiring diverse and unrelated businesses. It largely stayed beneath the radar and continued as a profitable public company until it renamed itself Wyeth and soon after was sold to Pfizer in 2009.

Textron is considered the first of the true conglomerates. The company was founded by Royal Little in the 1920s and became a conglomerate almost by mistake. Textron grew by using a provision in the tax code that allowed it to purchase money-losing companies and offset profits earned by another company owned by the parent organization. The strategy led to Textron straying away from the textile industry (hence its name) and venturing into unrelated businesses. But acquiring so-so businesses for their tax loss carry-forwards or surplus assets to monetize led to a collection of poor businesses. The sum was never equal to, let alone greater than, the sum of Textron’s parts. Little realized his mistake and changed course beginning in 1954. Textron purchased better businesses, including what became Bell Helicopter, and it remains a public company to this day.

Litton Industries introduced the issuance of shares as a new element to business acquisitions. Charles “Tex” Thornton intended to build a diverse company in the military electronics industry. Instead, a desire to expand led to increasingly-diverse acquisitions that ultimately strayed far from electronics. Thornton courted Wall Street to bolster Litton’s share price then used its higher-priced shares to acquire lower-multiple companies that juiced its own earnings per share. By the late 1960s the price/earnings arbitrage gig was up, and Litton’s stock price fell. Analysts realized the company produced more exciting accounting earnings than economic results. Litton was eventually acquired by Northrup Grumman, another defense company, in 2001.

Ling-Temco-Vought, sometimes referred to as LTV, pushed the limits of conglomerates even further. James Ling started as the sole proprietor of an electric company. Ling soon found out he could acquire companies using capital raised by issuing shares, borrowing heavily, and usually a combination of both. Accommodating public markets and the low interest rate environment of the 1960s allowed LTV to grow into a huge conglomerate by virtue of financial engineering.

In addition to the games played with complex financing schemes, Ling also introduced a new element to the conglomerate form. He actively sought out large enterprises to buy and then dismantle. The market rewarded the carved-up pieces with higher prices than as part of the whole, and the proceeds from these procedures funded the next deal. The financing structures were complex and often used convertible preferred stock that allowed earnings per common share to remain high and growing. It was a chimera. The house of cards came crashing down in the late 1960s when interest rates rose, LTV’s stock price cratered, and the company faced an antitrust lawsuit. It bit off more than it could chew with an exceptionally large acquisition that ended with Ling exiting the company. LTV stumbled along through periods of financial difficulty, including two bankruptcies, until it was itself carved up and sold off in 2002.

Gulf + Western was the creation of Charles Bluhdorn. Bluhdorn took a mediocre auto parts supply business and turned it into a darling conglomerate of the 1960s. The playbook was much the same as Litton and LTV. Bluhdorn used Gulf + Western’s higher-priced shares, convertible preferred stock, and other debt to acquire companies and increase reported earnings per share. The company took things a step further with creative accounting that masked the otherwise largely stagnant underlying businesses the company purchased. That included financial engineering with its purchase of Paramount Pictures in 1967 in which it sold off rights to movies and booked the total contract as income immediately.

The company made real profits in several takeover attempts that ended with others buying its initial stakes for a profit. These went into earnings too. Most of Gulf + Western’s business centered on unsustainable financial maneuvering rather than a focus on delivering real business results. In 1983, Bluhdorn died of a heart attack at age 56. Many of Gulf + Western’s businesses were sold off piecemeal. The company renamed itself Paramount Communications and was eventually sold to Viacom in 1994.

International Telephone & Telegraph, or ITT, was a company engaged in the business its name suggested. The company was taken to conglomerate heights by Harold Geneen in the 1960s. ITT used some of the same tactics as other conglomerates of this era, such as making acquisitions using stock. It seemed Geneen wasn’t as straightforward a conglomerateur as Royal Little, but he didn’t push it as far as Thornton, Ling, or Bluhdorn. Geneen took an established company and grew it to include finance businesses, car rentals, hotels, a homebuilder, a forest products company, and a bakery, among others. If not for antitrust concerns, ITT would have acquired American Broadcasting Company.

ITT’s strategy had two major drawbacks. The first was the same issue others had in buying less well-run companies. The second was its flawed vision of synergies. The company dreamed up ways in which subsidiaries under the ITT umbrella could transact with one another. But the companies gained nothing from being under one roof and may well have fared poorer because of it. ITT was broken up in two broad steps beginning in 1995 and again in 2011.

Teledyne: This last conglomerate was the brainchild of Henry Singleton, along with George Kozmetsky and George Roberts. Teledyne’s heyday was between the 1960s and 1990s. Singleton focused on the bigger strategic picture and gave subsidiaries autonomy to run their operations largely independently. Teledyne used some of the strategies employed by other conglomerates, such as the issuance of shares, which it did to great success. One of the defining characteristics of Teledyne was that it focused on buying better, cash-generating businesses. It then used the cash generated by those acquisitions to purchase the shares of other companies in the stock market. Finally, when Teledyne’s own stock became cheap, Singleton repurchased 90% of the company’s shares in the open market. Ultimately, Teledyne went too far in squeezing cash out of its subsidiaries, which hurt them competitively.

Lessons: Decentralized operations with centralized capital allocation is a powerful tool and comes with the added benefit of motivating managers with autonomy. Furthermore, it’s highly scalable. Good capital allocation also includes repurchasing undervalued shares.

The list presented here is by no means complete. There were dozens of conglomerates throughout the period of the 1950s to 1960s. Many were formed by insiders of the early conglomerates who struck out on their own.

If you enjoyed this post I’d appreciate you taking a moment to help me spread the word by sharing it. Thank you!

Stay rational! —Adam