Back to Basics #1: Return on Capital. Or, Why We Invest

Your neighbor's kid's lemonade stand and Berkshire Hathaway have this in common.

You’re reading the weekly free version of Watchlist Investing on Substack. If you’re not already subscribed, click here to join 2,600 others.

Want more in-depth and focused analysis on good businesses? Check out some sample issues of Watchlist Investing Deep Dives, a separate paid service.

For $20.75 per month, you can join corporate executives, professional money managers, and students of value investing receiving 10-12 issues per year. In addition, you’ll gain access to the archives, now 24 issues and growing!

Introducing a new series

In this new series, I’ll explore key investment concepts every investor should know. I hope it will be beneficial to newer investors and refreshing to the experienced. Leave a comment and let me know your thoughts. Thanks!

Return on Capital

The lowliest lemonade stand and the most complex conglomerate have one very important thing in common. They’re both in business to make money. Both companies (for even your neighbor’s kid’s lemonade stand is a company, albeit a very, very small one) employ capital with the expectation of receiving more capital in return. Investing is really that simple. Where it gets complicated is the fact that the economic landscape is ever-changing. To make it worse, accounting rules don’t neatly translate economic reality onto financial statements and spreadsheets. Enter the work of the business analyst. It’s your job - whether as a weekend warrior or paid professional - to figure it all out.

The Savings Account

Let’s back up a step and consider the simplest example possible: that of a savings account. It’s nothing very special. You put money in and the bank pays you interest, usually monthly, based on an annual rate. Assume you put $1,000 into your bank at a 4% interest rate. At the end of the year, you’d have 1,040.74, with the “extra” $0.74 due to the effects of monthly compounding.

In this ultra-simplified example your initial capital investment of $1,000 earned a return on capital of 4%.

Businesses are no different except the return on capital isn’t fixed (more on that at a later date).

Defining Return on Capital

I started with the savings account example because the term return on capital is not something all analysts agree on. Some use ROIC or return on invested capital. This definition incorporates all of the sources of capital a company has at its disposal. Typically the two major sources are equity and debt financing.

Others use ROCE or return on capital employed. ROCE seeks to examine only the capital actually employed in the business. Typical adjustments include removing excess cash and investments not needed to run the business. What defines excess is up to the analyst. We’re already beginning to see the complexity of investing emerge.

Variants of these two major definitions abound: return on average capital, return on incremental capital, return on tangible capital. All have their place.

I use return on capital employed as a general rule.

Example - Berkshire Before Buffett

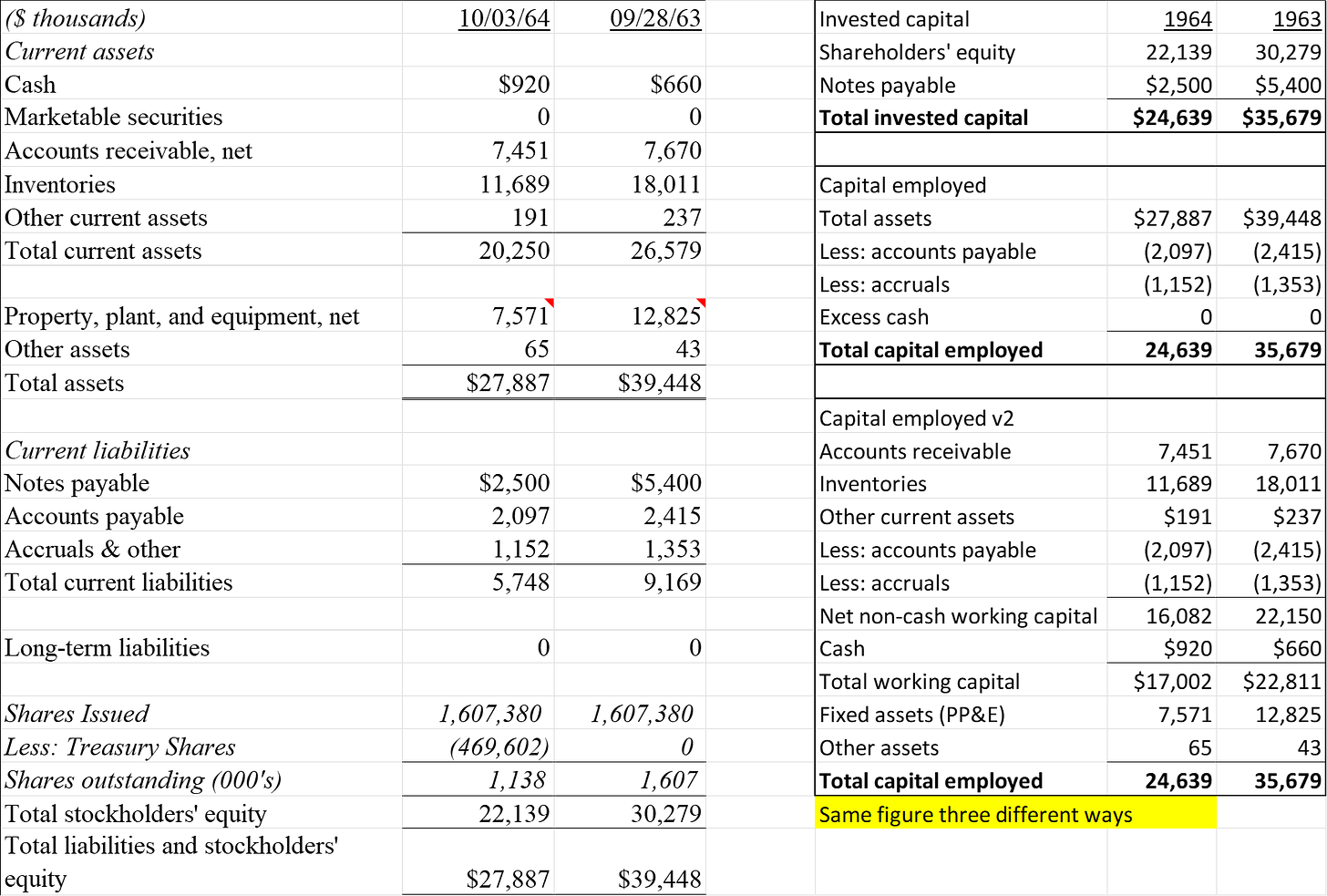

In 1964, the year before Warren Buffett took control of Berkshire Hathaway, the company had invested capital of about $25 million. This was in the form of shareholders’ equity of $22.1 million and notes payable of $2.5 million. Viewed from the standpoint of assets required to run the business, it had $27.9 million in total assets. From this one could deduct $3.2 million for accounts payable and accruals - essentially interest-free financing from suppliers and employees - to arrive at the same figure of $24.7 million. You can look at it a third way which is to build up from individual assets. In each case, we arrive at the same figure.

Berkshire in 1964 was no small business. It had lots of big buildings on owned real estate and huge amounts of physical inventory. The problem was that the assets generated terrible returns. For the year ended October 1964, Berkshire reported operating income (earnings before interest and taxes) of just $528 thousand on revenues of $49.9 million - a return of 1.75% on average invested capital.

Buffett’s Simple Formula:

I believe Buffett looks at businesses, at least at the surface level, using turnover and margins. To use the example above, Berkshire had an average invested capital of $30.2 million in 1964. Revenues of $49.9 million mean each dollar of capital turned over 1.65x. Operating income (EBIT) of $508 thousand is a margin of 1.06% on revenues. The formula is: $1.00 of capital generates $1.65 in revenue, which generates $0.0175 (1.06% x $1.65) in operating earnings. $0.0175 in EBIT / $1.00 capital = 1.75% pre-tax return on capital.

Shareholders would have been better off putting their money in a regular old savings account or a treasury note, which at that time yielded around 4%. In fact, this is basically what Buffett did. He entered the scene and shrunk the textile business, freeing capital that he then invested in marketable securities and businesses capable of generating higher returns.

Coca-Cola - A Slightly Bigger Lemonade Stand

Berkshire Hathaway accumulated 400 million (split adjusted) shares of Coca-Cola between 1988 and 1994. The total cost was $1.299 billion, a figure that remains unchanged today since Berkshire has neither bought nor sold a single share since acquiring the original stake.

What did Buffett see in Coke? Judging by results in the years before he bought it, he saw a business earning very high returns on capital. The analysis below isn’t perfect but even back-of-the-envelope math shows a superior company to Berkshire’s textile operations (which had wrapped up in 1985).

Using the formula above, average capital employed was $3.2 billion which produced revenues of $7.7 billion - a turnover of 2.41x or revenues of $2.41 for every dollar of capital employed. Operating margin was a very healthy 17.3%. So $2.41 of revenues generated operating income of $0.42 or a return on capital employed of 41.6%.

Notice that invested capital and capital employed are slightly different in this example. The advantages of using capital employed are apparent here. It’s clear that marketable securities are a superfluous asset that isn’t required in the syrup business. Neither is goodwill or intangible assets, which are largely accounting-related items. Deferred taxes are a liability, to be sure, however, a growing company like Coke could expect to receive this interest-free loan from the government for a long time to come, which means it reduced the net investment required to run the business. These are the types of adjustments that analysts quibble over. But at the end of the day, a business like Coke is so clearly a good business that the math doesn’t matter.

What Buffett saw in Coke was a core business earning very high returns on capital with a long runway to reinvest additional capital at similar rates of return. What’s more (and what probably finally got him interested) was the fact that Coke was divesting non-core assets like Columbia Pictures, which it bought in the early 80s) to focus on the core syrup business.

Summing Up

These two examples from Berkshire’s history illustrate the core of what investment is all about. Namely, to invest capital and receive a return on that capital.

Stay rational! —Adam

I'm curious if there are any helpful examples from Buffett on how to think about operating leases. I know he talks about capitalizing these leases (as now required on the BS) but does it also make sense to adjust the OE or EBIT, etc. for the current lease expense.

One of your best one’s yet