26: How To Calculate Growth Capex

Answering a subscriber's question for the benefit of W.I.N. readers

Watchlist Investing was never intended to be a source of always-timely or immediately actionable investment ideas. Rather, my goal has been to follow Charlie Munger’s advice1 in building a list of great companies to follow, secure in the knowledge that opportunities to jump in at attractive prices will materialize in the future.

This concentrates my research on finding and understanding good businesses regardless of their current valuation. Each month the list of case studies grows larger and subscribers to the full paid version have access to this growing valuable resource.

Subscribers can earn back the nominal cost of subscribing in just one issue. How? It takes 40+ hours of reading, researching, thinking, and writing to produce one W.I.N. newsletter. You can digest it all in less than an hour saving huge amounts of time.

Join the growing list of value investors, C-Suite execs, managers, and students by subscribing. I think it’s worth full price but as an enticement to you, my Substack readers, I’ll give you 10% off your first year. Use the code “Substack” at checkout.

A paid subscriber asked me how I calculated growth capex so I thought I’d use today’s Substack post to respond.

First, a definition:

Capex is short for capital expenditures. These are monies spent on long-lived assets. A new building, improving an existing building, a new truck. You get the idea.

Capex can be broken out into two broad buckets: maintenance and growth. Maintenance capex is simply bringing the condition of existing assets back to where they were at the beginning of the year. A building or truck doesn’t last forever; depreciation is a real expense. (A caveat here is that maintenance capex can be greater than depreciation if the cost of assets increases during the year. Same equipment, same unit output, higher cost. The reverse can also be true due to technology gains. But I digress…).

Anything above and beyond maintenance capex is growth spending. This is an investment in the future of the business. An additional truck, a new service center, etc. It can even be software. Here’s a table from the October issue on Old Dominion Freight Line:

You can see that in every year except 2020 the amount was negative. This means ODFL was investing more in its business than depreciation expense in efforts to grow the business.

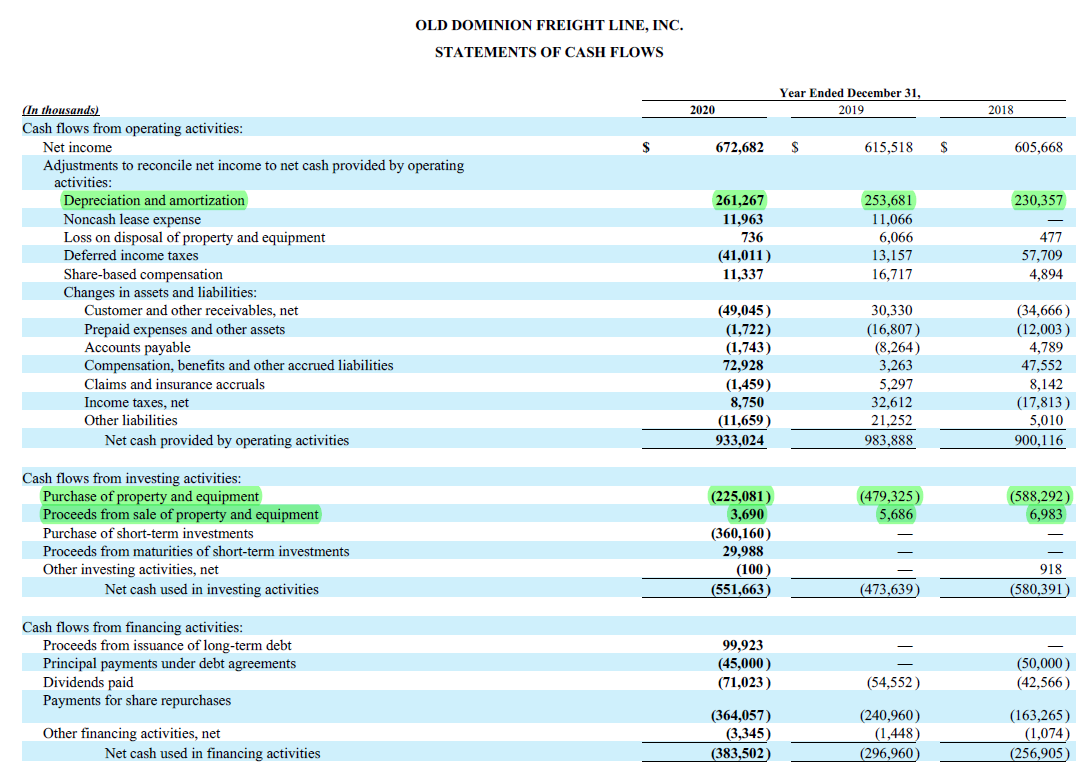

Here’s where the numbers come from in the ODFL 10K. We take depreciation/amortization, subtract purchases of property/equipment, and add back proceeds from the sale of property/equipment. (Note that the gain/loss on the sale of equipment is irrelevant because we only care about cash.)

We can see the growth in the business in the table below in terms of unit volume and revenues. We can also see the relatively linear relationship between capital spending and revenues in the bottom table. ODFL has gotten slightly more capital intensive over the past ten years but its margins have more than made up for it.

I really appreciate F.G. asking the question that led to this post. If anyone has questions about a specific company I’ve covered or even how-to questions like this where I go into how a number is calculated, I’d welcome an email or comment.

Stay rational! -Adam

Thanks Adam. How would you think about a company that build say a hydroelectric dam, with a very large initial capital outlay but much smaller ongoing maintenence expenses. Would you just consider the ongoing actual 'property palnt and equiptment' expeses in this case or still factor in depreciation? Thanks.