97: Aggregating My Thoughts On Capital Intensity

Thinking through the aggregates industry for my upcoming Deep Dives issue.

You’re reading the weekly free version of Watchlist Investing on Substack. If you’re not already subscribed, click here to join 2,100 others.

Want more in-depth and focused analysis on good businesses? Check out some sample issues of Watchlist Investing Deep Dives, a separate paid service.

For less than $21/month, you can join corporate executives, professional money managers, and students of value investing receiving 10-12 issues per year. In addition, you’ll gain access to the archives, now 23 issues and growing!

Calculating Capital Intensity

Investing is simple: you outlay capital with the expectation of a return on that capital. Simple math really.

But complicating the equation is accounting and inflation. Getting it right could mean the difference between a humdrum investment and one that makes a meaningful contribution to your portfolio.

Take the aggregates industry. The main product is crushed stone, gravel, and sand. It requires land containing minerals and equipment to do the extracting. Simple.

So now we have simple math and a simple business. But it’s not that simple! At least to me right now. The following examples use Vulcan Material (VMC 0.00%↑) to illustrate.

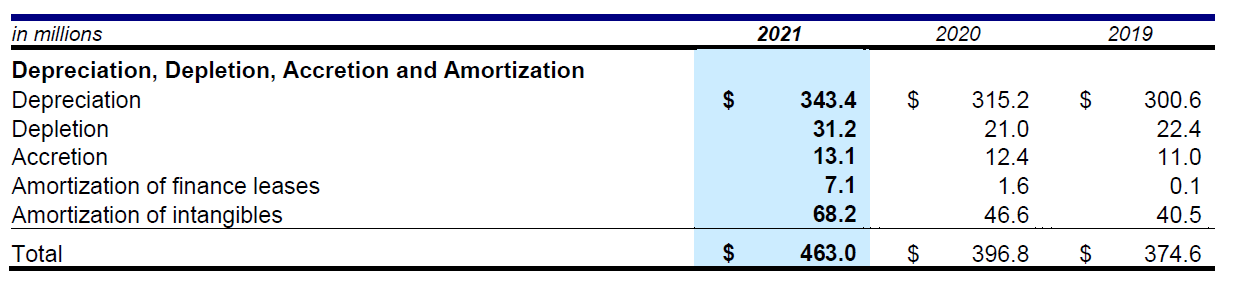

Getting Depreciation Out Of The Way

I can dispense with depreciation charges easily. Those are very much real as far as I’m concerned. As a rough check we can take the machinery and equipment value ($6,109.2 million) and add the value of buildings ($182.9 million) to get a total of $6,292.1 million. Divide that number by depreciation charges of $343.4 million and you get 18.3, which represents years. That’s smack dab in the middle of the useful life estimate of machinery and equipment listed in the footnote, which is what we'd expect to find.1

To Count or Not to Count, That is the Question

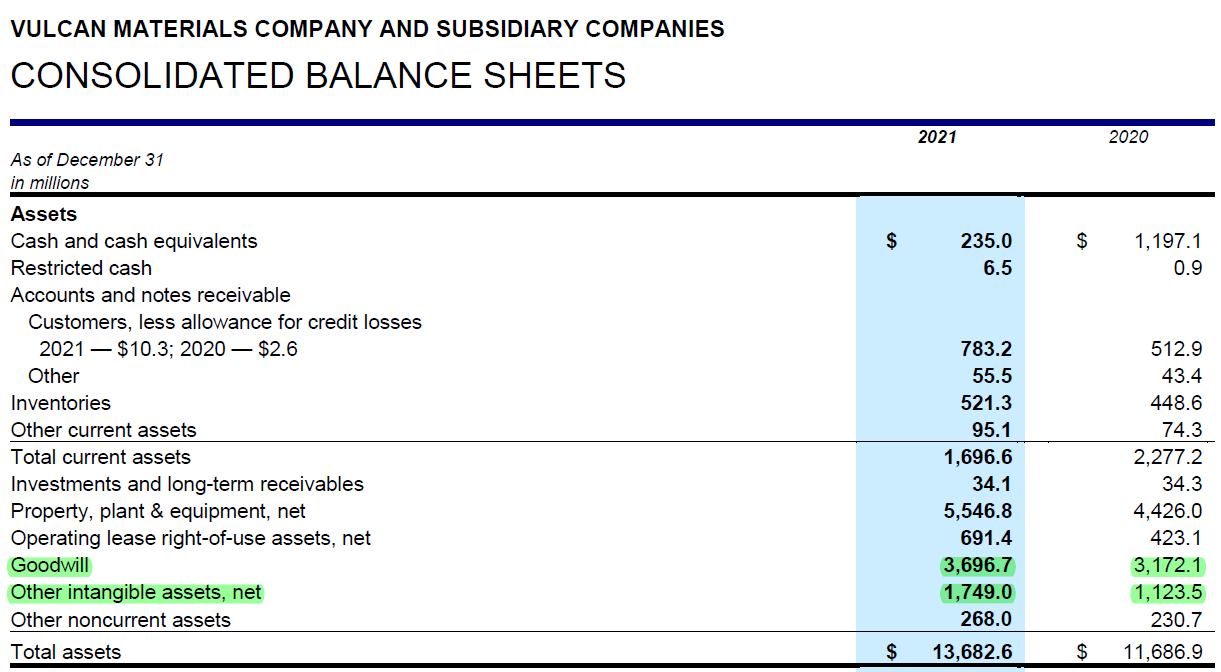

The question I’m facing right now is how to view goodwill and intangibles, and noncash charges like depletion. These aren’t small numbers.

At year-end 2021, goodwill and intangibles amounted to $5,446 million or 40% of VMC’s total assets. How these assets are treated will directly affect the calculation of return on capital. Including them will lower the calculated return by virtue of increasing the denominator. Conversely, excluding them will increase apparent returns. Hmm…

First Thoughts

I think it is appropriate to exclude goodwill and intangibles, and by extension add back any related accounting charges. Here’s my logic:

VMC 0.00%↑ lists its proven and provable reserves in its 10K. In the most recent 10K available (2021) it states that it has 15.6 billion tons of proven and probable reserves of aggregate raw material. We also know that it produced 0.22 billion tons of material in 2021. Some quick math tells us they have 70 years of production sitting in the ground. That’s a lot of rock!

Now VMC has hundreds of quarries but let’s simplify and assume they have just one huge operation with 15.6 billion tons of reserves, sufficient for the better part of a century of production. Will the company need to spend money on additional reserves to maintain operations? (I’m ignoring growth here, that’s separate. We’re just looking at a steady state, no-growth scenario.) The answer is no. Any discounted cash flow analysis would tail off way before they ran out of reserves.

Note that this analysis differs from a company that has intangible assets on the books as a result of purchasing businesses that require a lot of advertising/marketing to maintain. In those instances, I think it appropriate to include the goodwill/intangible figures because they must be replenished.

What About Inflation?

A nagging question I have is inflation. Some of the assets on the books of an aggregates company could be decades old. Their historical cost could be a small fraction of what it would cost to buy the quarries today.

Yet once those assets are on the books they don’t need to be purchased again. Going back to our one-quarry example, if we purchased a quarry 20 years ago and the going rate for quarries doubled, we’d still have the same cost for the material. Our production costs would likely have gone up, but our inventory of raw materials would act as an inflation hedge.

Revisiting Goodwill

Now VMC isn’t a one-quarry company. It has a couple hundred properties and is continually adding more. If management pays up for a new property, no matter how much above the existing accounting value of it, then that’s the cost. That’s the number upon which returns need to be calculated because it represents a real cash outlay.

So in this case I think it makes sense to keep goodwill as part of the equation but not adjust upward the existing properties on the books. In other words, Quarry A purchased 25 years ago might be identical to Quarry B purchased today at 2x the price. But from a cost-of-product standpoint, the “bargain cost” of Quarry A represents a real advantage.

Do you have direct experience with VMC or MLM? How should I think about historical cost, inflation, and goodwill/intangibles? Are there similar industries that could hold clues to untying this knot? Let me know in the comments section.

Thank you and…

Stay rational! —Adam

The case could be made that the replacement cost of these assets is higher and so depreciation is understated. You wouldn’t be wrong in that but I’m not getting into that level of detail here, nor do I feel it’s overly important to fret about if you get the big questions right.

Hi Adam,

1 Would you be able to do a case study of Buffett’s capital intensive purchase of BNSF?

2 Like SFX.ax which is a mineral sand company, most importantly is the Volume Risk, if no binding contract being signed to buy the volume produced, no equity investor would be interested.

3 FlightSafety, pretax earnings is 111 million and working capital is 202 million in 1995?

1995 next investment in fixed assets 570 million, Equipment at cost 894 million.

In 2007, when Buffett do the calculation of increments return, he first reached a figure current fixed assets after depreciation 1079 million, which I believe he use 273 simulator each cost 12 million as 3276 million equipment at cost in 2007 deduct the accumulated depreciation which is 384+923=1307 million and then deducted the 1995 equipment at cost 894 million to arrive at 1079 million current fixed assets after depreciation, basically asset based for capital intensive company?